From there, you know the story, he jumped to Formula 1, where his cars won two constructors' and two drivers' titles, establishing the mid-engine as the "must have" option for racing cars. It would be unfair to describe the Cooper as the first mid-engined racing cars, because similar solutions had already been tried by Benz and Porsche before the Second World War, but they did not have the same impact on the trends of the other participants as the Cooper. Perhaps we can't, especially, rule out the Autounion racing cars, but well, this is a subject that would take an article in itself, and we'll leave it for another day.

In the world of road cars the trend would take a little longer to arrive. The first mid-engined sports car marketed as a production car would be the 1966 Lamborghini P400 Miura (Miura a secas, later), with a transverse V12 placed behind the passenger compartment, and bodied by Marcelo Gandini.

At that time Gandini saw the potential of mid-engine car design, as it allowed aesthetic licenses never dreamed of before. But he did not fully exploit it with the precious Miura.

It would be a year later, in 1967, when the story we are going to tell you would be born: the design of the "wedge" or "arrow" cars, better known by its English term Wedge. Its creator would be the Lamborghini Marzal, also by Gandini, although it did not fully comply with one of the bases of this design: front bonnet aligned on the same plane as the windscreen.

The "Wedge design" trend would gain strength during the following years, becoming key for all the concept cars of almost all the manufacturers around the world, before taking a radical turn. After the eighties, many manufacturers would begin their return to organic shapes from the nineties onwards, abandoning straight lines in favour of curves. But a small group of the most advantaged would keep the design alive up to the present day.

Let's take a closer look at this unique line of design.

In the early 1960s, it was clear to almost all manufacturers that the future of sports cars lay in creating mid-engined cars. In Italy, a new movement was beginning to emerge among young designers to create shapes more suited to the distant future than to the times.

Placing the engine in the central part allowed much shorter, steeper bonnets, and better integrated with the front window. It was also a time when aerodynamic studies were beginning to pay off, and designers were beginning to realize that sharper, more integrated shapes could have better results.

The shape of racing cars was, therefore, going to fire the imagination of many designers. The first firm step with a concept prototype was taken by Marcelo Gandini. After finishing the Miura, and responding to the dictates of Lamborghini, he began to think about a two-plus-two-seater GT car. Ferrucio Lamborghini was not convinced by supercars like the Miura, and preferred more pure Gran Turismo cars.

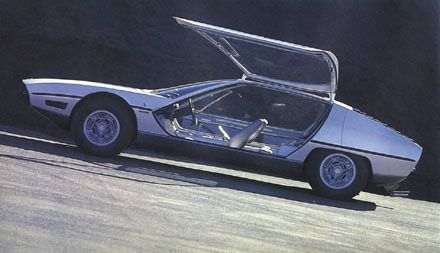

Thus was born the Lamborghini Marzal, which anticipated what was to come in the form of the Lamborghini Espada. It was presented in 1967, with a mid-rear engine, practically on the rear axle, with a tremendously sharp nose and two gull-wing doors that would be replaced before it went into production.

It was sharp, but its windshield was not aligned with the hood, so we can not consider it as the first pure "wedge".

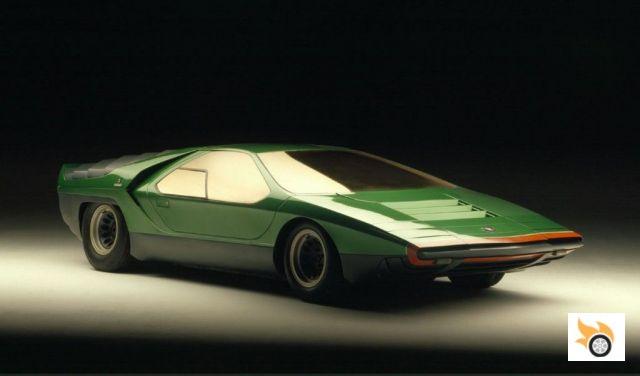

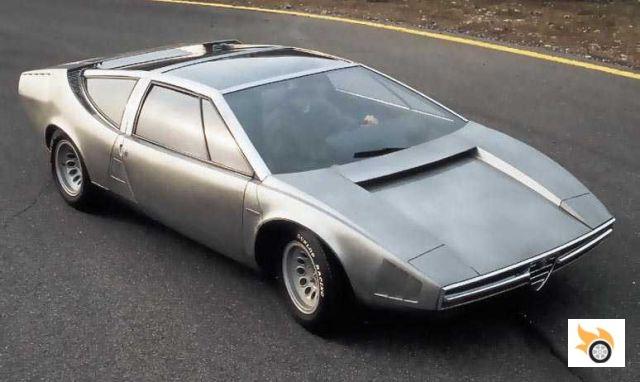

This honour goes to the Alfa Romeo Carabo. Also created by the great Marcelo Gandini, the Carabo was a further step in the knowledge that Gandini was accumulating. The Miura, also designed by him, had shown aerodynamic problems in its front end, with lift unloading the front end.

Reflecting on the problem, Gandini envisioned the Carabo by synthesizing the entire front end into a single piece (the windshield barely formed 14 degrees with the hood) to turn it into a sort of "giant shovel" with which to attach the nose, while the rear, like a louvered blind, had a "coda tronca" finial that also favored aerodynamics.

The Carabo did not stop there, and for the first time it had integrated for the first time doors that would later be integrated in the Countach, also designed, of course, by Gandini.

The Carabo was mounted on an Alfa Romeo 33 Stradale chassis, another aesthetic and sculptural jewel, but which seemed to be from another era when compared to the "techno" design of this green car.

In this way, the Carabo would become, in 1968, the "official percussor" of the "wedge" cars. But this is where the disputes about the rightful "owner" of the idea begin. As you may well remember, Giorgieto Giugiaro was working as the boss at Bertone when Gandini arrived there.

Giugiaro was working on various sketches for Bizzarrini, who was pursuing the design of his first supercar. Among those sketches was one that was to be taken to production, and another that would remain a concept for the time being. The sketch of the car that was to be produced was practically identical to the design of Gandini's Miura, something Giugiaro never tires of recalling.

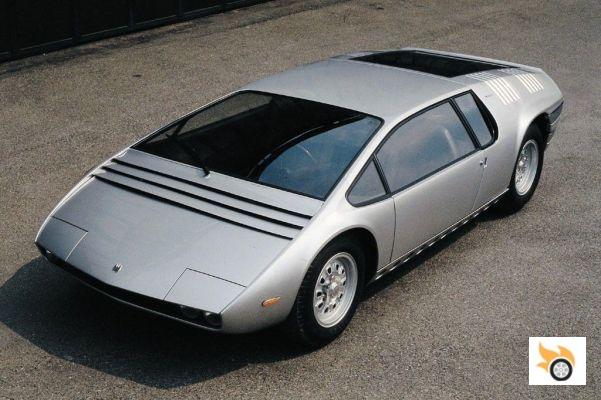

Interestingly, Giugiaro was leaving Bertone to set up his own design consultancy, ItalDesing, whose first job would be for Bizzarrini as well. After seeing Gandini's Miura, Giugiaro decided to take a step into more aggressive and contemporary design, creating the Bizzarrini Manta.

The Manta, mounted on the same mechanical base as the Bizzarrini 538 racing car, showed a wedge-shaped design, with a windscreen extending the bonnet and a truncated tail, and made an appearance at the 1968 Turin Motor Show, a few months after Gandini's Carabo.

Giugiaro has never wanted to enter into discussions on this subject, but the fact that he and Gandini worked together had something to do with the fact that both designs shared the idea of the windscreen and bonnet on the same plane, something that would otherwise be difficult for both of them to come up with at practically the same time.

But beyond the actual authorship of the particular design, the Manta was only the second clear sign of a new era in automotive design.

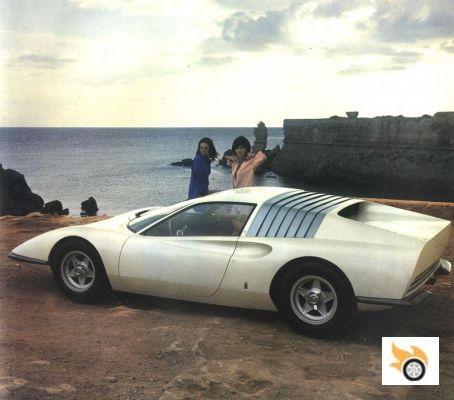

But sometimes design converges because of the ideas of the time. At the Paris Motor Show, Pininfarina showed the conceptual Ferrari P6, which, although it didn't exactly follow the same language used by Gandini and Giugiaro, also used strong references to the sharp nose and sharp planes.

Pininfarina's inspiration came from racing, where wedge-shaped designs with truncated rear ends were beginning to cause a real furore. The P6 in any case lacked the windscreen aligned with the bonnet, but it would serve as the basis for the 365BB that so many people would fall in love with in 1971.

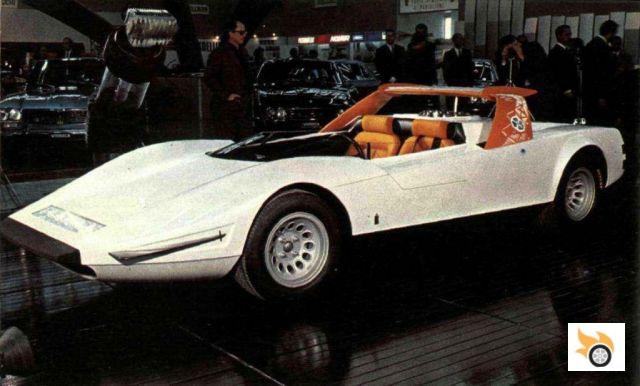

But the wedge-shaped surprises at the Turin Motor Show didn't end there. Not content with bringing the P6, Pininfarina also brought a prototype for Alfa Romeo, under the name of P33 Stradale, that same 1968. It was a two-seater racing roadster, but capable of being registered for road use, with a very peculiar solution for the headlights, configured by a single central optical group with multiple elements.

The furor unleashed by the "wedge" designs was such that all the design houses and manufacturers of the globe saw that this was the new trend to dominate the "concept" saloon cars in 1969. Consequently we would see an explosion that would lead to cars like the Abarth 2000 Pininfarina, Giugiaro's Alfa Romeo Iguana and many others.

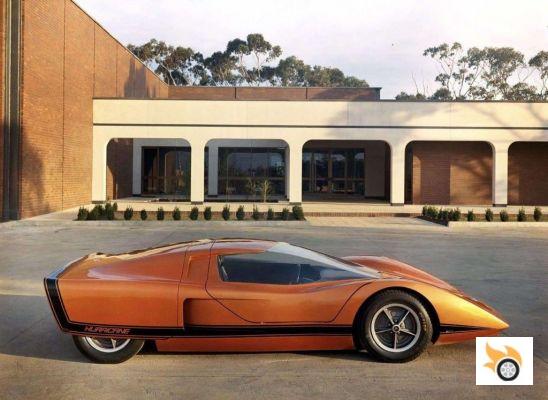

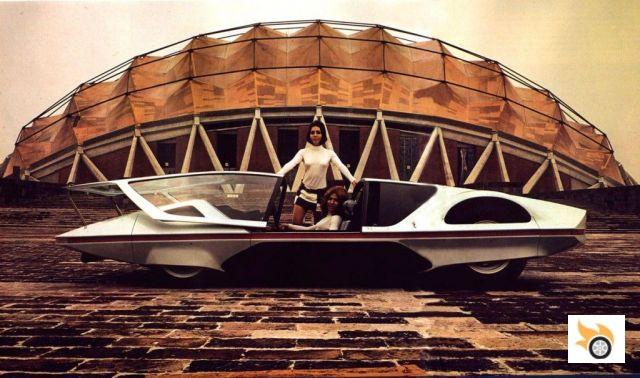

But the impact of the wedges would reach far beyond Europe. Holden saw a luxury opportunity in these new shapes, and created the Hurricane concept car, which you have below.

The Hurricane combined a peculiar access to the cabin, similar to that used by Pininfarina in the Abarth, with a carlina that opened like an airplane, and extremely well-kept proportions, with virtually no rear overhang, and a very, very sharp nose. Even in 2012 it still looks modern, sleek and attractive to us.

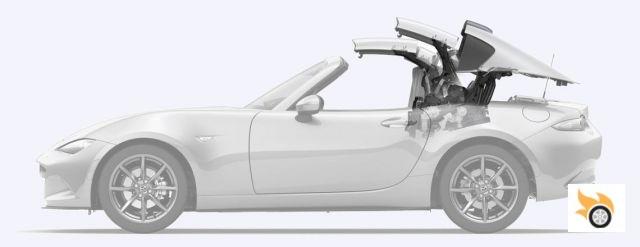

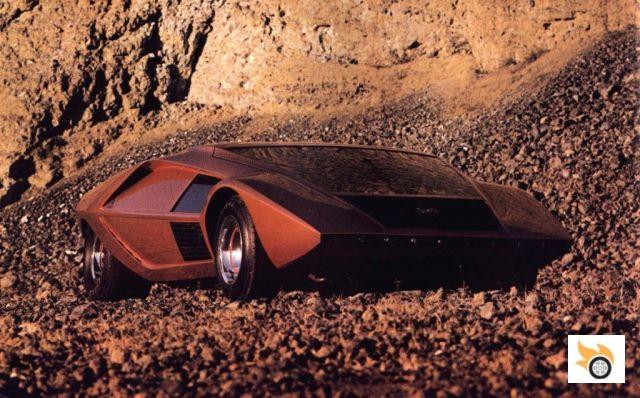

Gandini would stay relaxed during 1969 at Bertone to return in 1970 taking another new step forward with the spectacular conceptual Lancia Stratos Zero. It was an even more daring step in applying a unique wedge shape to a car, and integrated innovative solutions, such as access to the cabin through a hatch that incorporated the windscreen, and opened up the steering wheel.

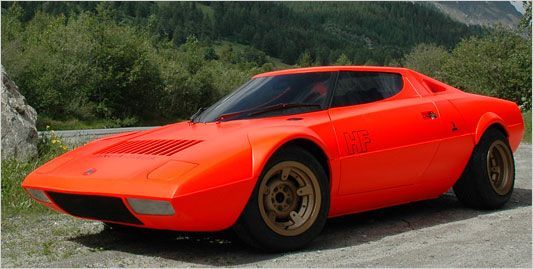

And of course, you know how this story ends: Lancia wanted a production version for its "squadron corse" HF, which also drawn by Gandini would end up being the production Stratos, one of the best cars of all time, without a doubt.

The Stratos was to be Gandini's crowning glory, and he would return to Lamborghini after the Miura to create the successor to the raging bull's supercar in 1971. Taking many ideas from the Carabo, which would never be produced for Alfa Romeo, Gandini and his team at Bertone would come up with an extreme, brutish and beastly car.

Thus was born the Lamborghini Countach, the most extreme evolution of the wedge concept. Lengthened to accommodate the enormous Lambo V12 longitudinally, and with guillotine opening doors, the Countach would give many headaches before reaching production, but it would rise, perhaps, as the peak of the "wedge design", to the point of being unequivocally associated since then with the Lamborghini DNA.

We could go on and on about dozens of prototypes from the seventies with wedge shapes. Of all of them we highlight the most extreme conceptual example: the Ferrari Modulo by Paolo Martin. So extreme was the Modulo that Pininfarina itself didn't want to get too involved in the project, leaving Martin to sign the car as his own "with the support of Pininfarina".

But the success of the design and its media impact were such that it soon became one of Pininfarina's masterpieces. Presented in 1970, it cannot be considered as a forerunner of this style of car, but it is one of the most extreme evolutions of the "wedge" concept, and of the principles of furniture design at the time, with shapes assembled as modules.

It was not intended to be taken into production, but its genetics would be noticed in later works by himself and others.

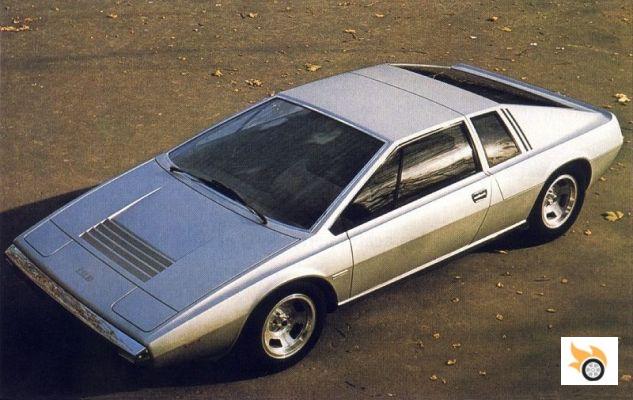

The impact of the "wedge" design in the salons soon began to be transferred to the production of street sports cars. We saw the birth of the aforementioned Ferrari 365BB, the Lotus Esprit, the Countach, the TVR "wedge" (Tasmin). As we said, we could spend hours talking about each of the designs, and this article would be endless.

Unfortunately for the fans of these sharp and polygonal shapes (among which I am), the evolution of shapes and tastes would make that in the mid-eighties the world of the automobile would return to the organic and curved, cyclical as always, and prey to the fashions started by the visionaries.

But a small handful of designers and brands had already integrated the "wedge" into their aesthetic DNA, and have reached the present day.

A good example is Lamborghini. You can look at a Gallardo or an Aventador, and you can trace its origins to the work of Gandini (and Giugiaro). Nowadays we are facing so many aesthetic crossovers that sometimes the "wedge" can be seen intermingled with more evolved forms. A 458 Italia, for example, is a healthy example of a sharp, but not quite wedged, car that mixes curved surfaces with wedged overall shapes and volumes.

We have other good conceptual works. The Brivido or the Fazer Nash Namir, also by Giugiaro, which illustrates these lines at the top, are two examples that the "wedge" still has a long life ahead of it, especially if it knows how to adapt to new trends and needs.

Because if there was a downside to the wedge shape, it was that it made for somewhat extreme cabins, the habitability of which was compromised. In addition, designers would soon realize that you could achieve larger cabins with better aerodynamics by creating "water drops" shaped on the body (just look at an Audi R18 to understand what I'm talking about).

A design story that caused a furor to disappear progressively. But like any design trend, sooner rather than later it will be back in fashion. Its original creators from time to time try to recapture it, and perhaps with the massive arrival of electric cars we can pick up this exciting vision of the world of four wheels where we left off.

Report originally published in December 2012, recovered for Pistonudos.